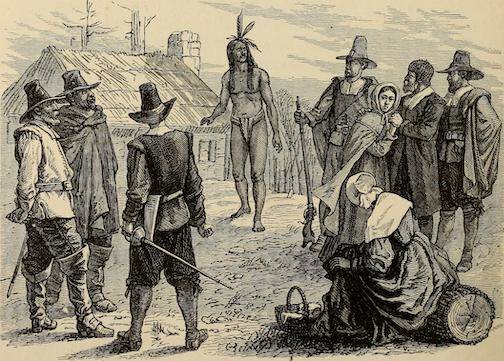

Every year as Thanksgiving approaches, it’s comforting to fall back on that image of the First Thanksgiving we learned in grade school. The Pilgrims, half starved after their first crops failed, are helped by friendly nearby indigenous people led by that noble warrior Squanto, who teaches them how to catch fish, hunt wild turkeys and grow native crops. They all then gather for an abundant feast of thanksgiving in the fall of 1621.

Of course, most of that is simply beautiful mythology, maybe better described as a whitewash. The truth is quite a bit darker. Squanto is an anglicized version of Tisquantum, his actual name. He was a member of the Patuxet tribe that lived in what is now southern Maine.

A dozen years before the Pilgrims set foot at Plymouth Rock, he was kidnapped by English sailors in 1608 and forced to be a slave first to some Christian monks in Spain, who then sold him to wealthy traders in England. His English masters sent him back to the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1619, where he quickly discovered that virtually his entire native tribe had been wiped out by diseases, mostly small pox, that the white settlers brought to the New World.

Because he had no family left and because he could speak English, he gravitated to the newly arrived Pilgrims, who were in distress and clearly needed his help. But just a year later, Squanto died at the estimated age of 37 of a painful white settler disease for which his body had no natural immunity. The Pilgrims prayed Christian prayers over him and buried him in their community.

Think about that for moment. A man is captured and enslaved by treacherous foreigners who take him thousands of miles away to be their servant. But instead of bitterness, anger and hatred, he joins and helps a group of foreigners who had taken the land that belonged to his ancestors and brought the diseases that killed them.

As I reflected on the rather brutal story of Squanto, I realized that there was a parallel to things that happened here on our beautiful Rock not that long ago. When Joseph Whidbey sailed into Penn Cove in 1792 as part of his survey of the island for Capt. George Vancouver, he estimated that at least 600 native people lived in structured villages around the cove; it may actually have been as many as 1,500.

Archeological research has shown that Skagit people had established permanent villages on Penn Cove as early as the year 1300. The reason was clear: It provided an abundance of food from the sea and land as well as nutritious plant food such as camas bulbs and bracken ferns. And, equally important, it provided considerable distance from aggressive enemy tribes that lived across the water on the mainland.

When the Donation Land Claims Act of 1850 opened Whidbey Island to white settlers from the east, the indigenous people soon found themselves surrounded by new neighbors with strange ways. The settlers believed in private ownership of land; the natives had little or no concept of such things, usually sharing everything together.

As folks like the Ebeys, Hancocks and Coupes arrived, they were generally greeted in a friendly manner by the indigenous residents, who often brought them food and even clothing to welcome them. Despite that welcome, however, the white settlers had doubts and worries about the more aggressive mainland tribes they had been warned about – a well-founded fear, as it turned out. Some built block houses – a couple of which still survive – as defensive shelters should local indigenous people go on the attack, though no such attacks ever happened.

Rebecca Ebey, the sickly first wife of Col. Isaac Ebey, for whom Ebey’s Prairie is named, depended on the help of native women as she suffered through a difficult pregnancy and then died of tuberculosis in 1853. Those women considered her their neighbor.

So here’s how I reflect on all this: White settlers arrive on the Rock and promptly declare themselves the new owners of land that had been occupied by the indigenous people for at least 500 years. And yet, the native people welcomed them, helped them and brought them gifts to get through the harsh first few years.

Then, in relatively short order, the white settlers decided the indigenous people could not be fully trusted and should leave; there was no room for them. And, within the first 50 years, many of the local native people had died of white settler diseases. It’s no wonder that many of the rest left willingly to live on a reservation off the Rock, away from the white settlers.

As we gather for this Thanksgiving, we ought to recall just how this holiday began – and who really made it possible. And on the Rock, we ought to remember those who helped the first white people settle here. And not conveniently forget what happened to them.

Here’s an excerpt from an article published in the Farm Bureau News in 1935 that succinctly answers that question in a not-so-elegant fashion:

By 1900, “the Indians had already come to occupy much the same position in the (Penn Cove) community which the Negro occupied in the Old South after the Civil War. The women took in washing and did housework; the men …hired out on farms or as help in stores, and served as ferry men between the island and the mainland. By and large, the natives were regarded with an attitude of mixed paternalism and tolerance.”

Harry Anderson is a retired journalist for the Los Angeles Times who lives in Central Whidbey.