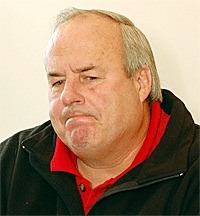

First-time candidate Phil Collier has had some problems complying with the rules that govern political campaigns, though he describes them as small, nit-picky items that have nothing to do with the real issues.

Collier, an Oak Harbor businessman, is running as an independent candidate for the Island County commissioner seat currently held by Democratic Commissioner Angie Homola. City Councilman Jim Campbell and Oak Harbor Chamber of Commerce Director Jill Johnson are also running in the crowded race as Republicans.

Collier started his campaign aggressively, with big ads in a local shopper and campaign signs dotting the landscape before any of the other candidates. But while all the other candidates submitted details about contributions and expenses to the state Public Disclosure Commission, information submitted by Collier was noticeably absent.

Collier said he hired his longtime attorney, Christon Skinner of Oak Harbor, to advise him on the campaign.

“I was my first time running for office and I wanted to make sure I got everything just perfect,” he said.

But it didn’t turn out that way because of a miscommunication. Skinner said he assumed that Collier’s treasurer, his wife Kathy Collier, would be submitting the reports, which is the usual practice. But the Colliers thought Skinner was doing it, so it didn’t get done until last Thursday.

“From my conversation with a representative from the Public Disclosure Commission, they will be satisfied with our explanation of what happened and even though the filing is late, they don’t believe it was anything actionable,” Skinner said. “So it was simply a misunderstanding and Mr. Collier is in compliance now.”

The records show that Collier has placed $8,150 of his own money in his campaign fund, loaned himself $6,000 and owes $12,625.23. In an interview Monday, he said he’s not going to accept contributions. He said he sent back dozens of donations he’s received with a message asking his supporters to contribute to charity on the island instead.

“With the economic downturn and so many people struggling, I just don’t feel comfortable with asking people for money,” he said.

Nevertheless, the public disclosure documents indicate that Collier actually missed two deadlines for submitting necessary forms to the state, according to Tony Perkins, the lead public finance specialist with the Public Disclosure Commission. Collier submitted his C-1 candidate registration form on March 21. He was obliged to also submit at the same time a C-4 form detailing receipts and expenditures to that point.

Perkins pointed out that Collier had purchased a $1,275 ad from a shopper before March 21. Then Collier was supposed to file again on April 10, Perkins said, but again nothing was filed even though he spent $2,250 on another shopper ad and smaller amounts on labels and a parade entry fee.

One of Collier’s political rivals expressed concern about the disclosure oversight. Johnson said full disclosure shines a light on the campaign process and on those who may try to influence it.

“Campaign finance laws came about at the request of the people. We wanted more transparency in the political process,” she said. “The decision to not adhere to the disclosure laws that govern a campaign brings into question any candidate’s commitment to open government.”

Homola said she understands that people make mistakes, but she feels what’s important is how the candidate reacts. In Collier’s case, she said, he blamed his attorney after the oversight persisted for six weeks. She pointed out that his campaign flyer claims “the buck stops here.”

“What I’m more concerned about is that his campaign business model involved gambling with debt,” she said, “and he said he wants to run the county like a business. That kind of business plan doesn’t work with the people’s money.”

It appears that Collier’s brochures may also be out of compliance with the law, though at least one other candidate has the same problem. Perkins said there is supposed to be a statement on the first page of a campaign brochure that includes who paid for the advertisement and the sponsor’s address. On Collier’s brochures, the statement was on the last page.

“I don’t know anything about that,” Collier said. “I just brought it to the printer and said, ‘Do it right. Do it legal. Do everything that should be done right.’”

Campbell’s campaign flyer has the same oversight. Johnson conceded that the issue of having the disclaimer in the right spot on a brochure is petty and she doubts voters will care.

Collier has also been criticized for his campaign signs, which some people wrongly thought violated the law because they didn’t include his party affiliation. Perkins explained that a candidate’s campaign signs need to include a party affiliation only after he or she officially files for office during the candidate filing period, which is May 14 to 18, and chooses a party affiliation. As a result, Collier’s signs are in compliance unless he writes in a party preference when he files; Perkins said independent candidates can choose no party preference and avoid the requirement.

While Collier may have violations, Perkins said it’s unlikely that the office would investigate unless there’s a complaint made.

The Public Disclosure Commission’s role is to collect reports from political candidates and ballot measure sponsors regarding campaign contributions and expenditures, provide these reports to the public and investigate any suspected violations; the agency was created in 1972 by a voter initiative and is currently chaired by Oak Harbor resident Barry Sehlin, a former state representative.

Perkins said the state has among the oldest public disclosure laws in the nation. Because of this history, he said the vast majority of candidates are well aware of — and follow — all the rules and technicalities.

“Public disclosure is just part of the political culture,” he said.