The bronze sculptures by Georgia Gerber have captivated passersby in Washington for nearly four decades.

Her more than 50 public installations statewide include “Rachel the Pig,” the mascot of Pike Place Market, baboons at Woodland Park Zoo and the dancing girl trio on Colby Avenue in Everett.

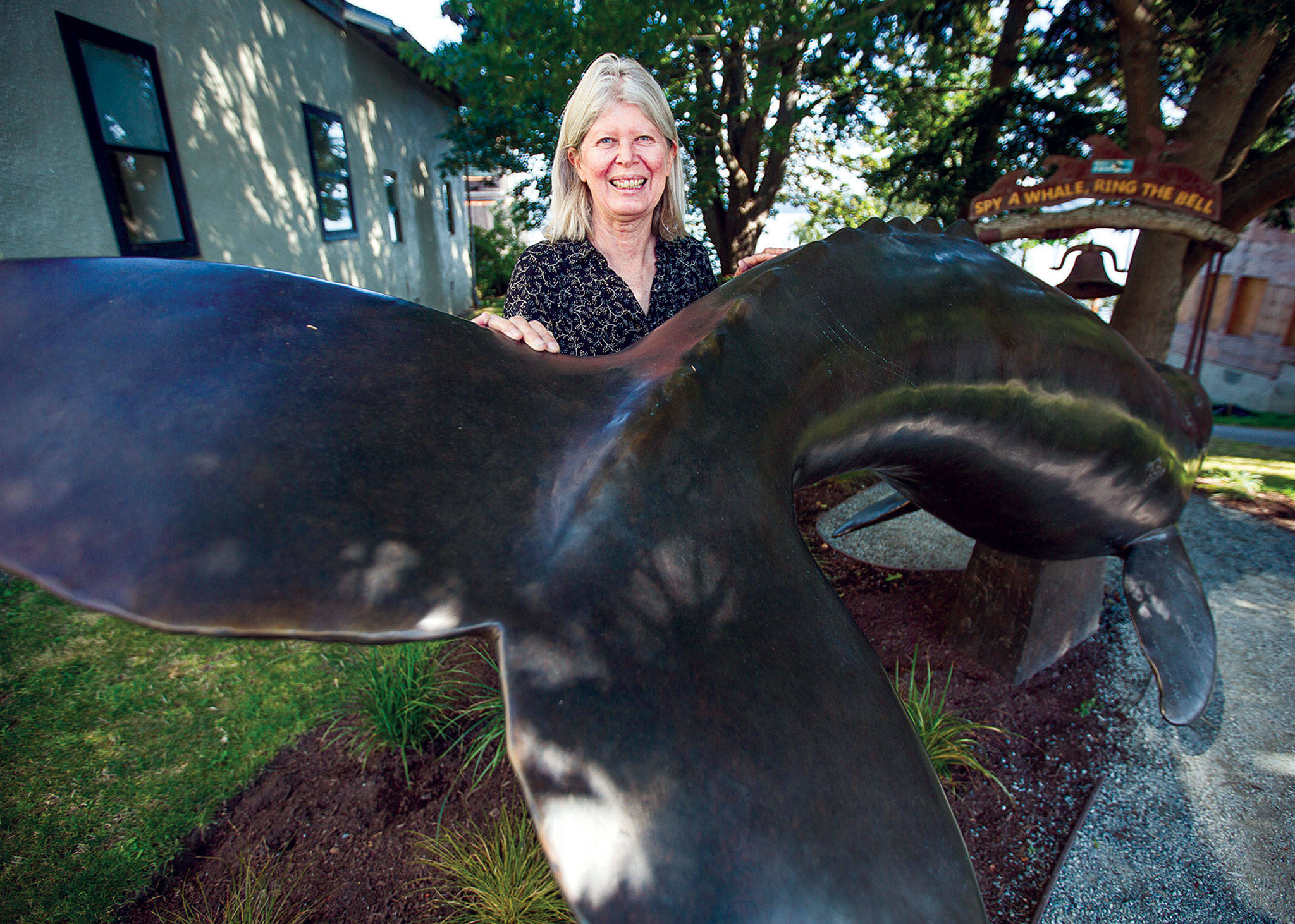

A new sculpture is the 12-foot “Hope the Whale” overlooking the waterfront in Langley.

Gerber, 65, and her husband, Randy Hudson, moved from Seattle to Clinton in 1983 and set up a studio, foundry and a stable.

Randy, her right-hand man, is a musician in the island-famous band The Rural Characters.

Foundry assistant Virginia Keck has done her fabrication and finish work for more than 35 years.

As a fundraiser for various island nonprofits, Gerber created the Christmas Sculpture Project, where a donation of $200 gets collectors a small pewter figure every year that is kept secret until the seasonal reveal.

When not sculpting, Gerber said she enjoys spending time with her grandchildren and riding her horse.

She said it has taken her a long while to realize that she observes things differently than most people.

“I see shapes and forms more than details, and that’s what I focus on when sculpting,” she explained. “To me, it really shows in my work. In many of my pieces, you could take away the parts that identify them as figurative and be left with a sort of abstract form that still works sculpturally.

“I think that is a lot of the attraction people have for my work, even if they don’t realize it.”

“I also love whimsy, which I think of as playful or fanciful rather than comical,” Gerber said. “There can be the whimsy of three girls dancing on a sidewalk, or a cow and calf at home in the middle of an urban shopping center that was once a dairy farm. But my most obviously whimsical sculptures have to be the series of ‘Dancing Rabbits.’”

“I started long ago with a pair waltzing at the “Harvest Moon Ball” and have continued on with different dance poses every two or three years since,” she said. “It’s a challenge to try and adapt animal anatomy to human movement, but the blending creates a whole other sort of visual whimsy on top of just the idea of them dancing.

“I knew early on that I wanted to work life-size, which can be very expensive to produce in bronze,” Gerber said. “So I learned how to cast my own work, which really helped build my career.

“We cast for about 35 years, but have now transitioned to partnering with Reinmuth Bronze in Eugene. “

Knowing the difficulty and demands of the whole foundry process informs her sculpting style somewhat, not in any kind of limiting way, but in a way that makes the translation of clay into bronze more fluid, she explained.

“I have always preferred my public work to be as accessible as possible. I like that people, especially children, can touch it and get involved with it. So whenever possible I place it directly in a site and seldom on pedestals.”

Gerber grew up in rural Pennsylvania riding horses and tending animals on a small farm with her twin sister.

“Back then, we actually had art in high school and there was clay available, and I found I enjoyed three dimensions,” she said.

“One of my first pieces was a little owl.”

Gerber said she headed west for the master of fine arts program at the University of Washington.

“It was a difficult time for me because the sculpture department was not oriented toward the kind of figurative work I was doing,” she said. “But in the end, I think that was actually helpful, since it forced me to explore different ways of thinking about sculpture and combining styles.

“I’m sure that lesson later inspired pieces like Triad for the Everett Public Library, with realistic but minimalized harbor seals cutting through three pillars that are architectural in nature, but also somewhat natural looking.”

Gerber said making art brings her joy, “and to think that my art brings joy to others seems to me about the best bargain ever made.”

The early years of trying to make a living were hard, and Gerber said she questioned her life choices at times.

Somehow, though, whenever it seemed nearly hopeless, that call would come in from a gallery about a sale, or one of the seemingly endless applications for public art commissions would actually end up with her being selected, Gerber said.

“I am very grateful for all the support I have received.

In Langley, Gerber’s sculpture of a teenage boy leans against a railing and looks out over Saratoga Passage, with his dog waiting by his side.

“Randy and I sit in that little First Street Park sometimes and watch people interact with the piece,” she said. “One time, a tourist used broken English and motioned to ask me to take a picture of him and his family gathered around the piece.”

“If I ever wonder why I do what I do, I’ll just go sit there on a busy day.”

Retirement and what that might look like is a topic of discussion lately, she said.

“Like a lot of self-employed people, we’re faced with how to wind things down after working so hard to get where we are. Not sure how that’s going to play out. I have grandkids, so I am spending more time with them and slowing down with the studio work. I really get a kick out of being with them because any sculpture they see, whether it’s mine or not, they go, ‘Nana, did you make that?’”

“They know Nana makes sculptures.”

Gerber said the reasons she became an artist haven’t changed

“But like of a lot other things I still love to do, it’s clearly going to have to be at a more leisurely pace.”

Gerber sculpts in oil-based clay that never dries out, which is a lot more convenient than the natural clays she previously used.

“But to get from a completed clay work to a bronze sculpture, there’s a whole lot of skilled foundry work that goes on.”

I have had wonderful assistants over the years, and Randy has been a huge part of making it all happen,” said Gerber.

“He’s the foundry man, bookkeeper, photographer, mold maker and so much more.

“He’s been what every artist needs in their lives to free them from all the necessary practicalities of this business,” she said.

“Sometimes his level-headedness gets in the way, though,” Gerber said. “While he does tolerate my having horses in our pasture, he nixed my proposal of life-size bronze stallions crashing through the second story wall for a casino in Reno.