A $66,000 feasibility study approved this week may determine the future location of a proposed sewer treatment plant in Freeland.

Over the next 60 days Seattle-based Pacific Groundwater Group will perform hydrogeology tests for the Freeland Water and Sewer District on a 24-acre property between Highway 525 and Scenic Avenue. The results will decide whether the site is a suitable location for a treatment plant that would serve the commercial core and potentially other areas in the future.

“If everything pans out, we’ll buy the property,” district Commissioner Lou Malzone said.

Money to buy the property will come from $3.5 million in state grant funding, which was secured years ago for an earlier sewer effort.

The price tag of the property, owned by Jerry Stonebridge, was agreed upon in a purchaser’s agreement of $800,000. It was signed by Malzone, but the sale will only move forward if the study determines the property is suitable and the entire board approves the deal.

One of the largest criteria is that the site’s soil meet certain daily drainage capacities. District officials are hoping the site will support drain fields that can handle at least 100,000 gallons per day of treated effluent.

According to district Manager Andy Campbell, the average water usage in the commercial core was about 34,000 gallons per day in 2014. Similarly, over the past three years, the lowest usage for the whole district was 77,000 gallons in December 2013, and the highest 169,000 gallons in July 2013.

“It should handle all the commercial core’s needs,” Campbell said.

The proposed treatment plant could be expanded on the site to handle later phases, but how much drainage it can support remains an unknown. It’s largely agreed that additional sites may be needed in the future.

“Disposal is the issue,” said Dave Wechner, Island County’s planning chief.

The feasibility study may or may not satisfy all of Freeland’s needs under its existing boundaries, but those may change. The county is updating the comprehensive plan, and changes in population growth estimates may indeed result in a boundary reduction, he said.

The district has identified several other possible drainage sites should the study show the Stonebridge property to have lesser drainage capacities than hoped, but the idea is to use it as the primary location for Freeland’s treatment needs.

“We’re not just planning it for one little group (the commercial core), it’s for everybody,” Campbell said. “We’re just trying to get it started.”

The conversation and effort to build sewers in Freeland has spanned decades. Proponents say they will open the doors for growth and development through the expansion of business opportunities while simultaneously addressing several clean water issues. But the move for sewers is more than a simple desire for infrastructure. The Growth Management Act of 1990, the landmark legislation that guides development throughout the state, requires communities of intense development designated as non municipal urban growth areas or an NMUGA, such as Freeland, to both plan and build sewers.

The sewer district and the county have worked toward that goal for years, but a plan in 2005, and a significant effort in 2010 — widely regarded as the $40 million plan — failed to materialize. Cost, scope and public outcry killed the most recent project.

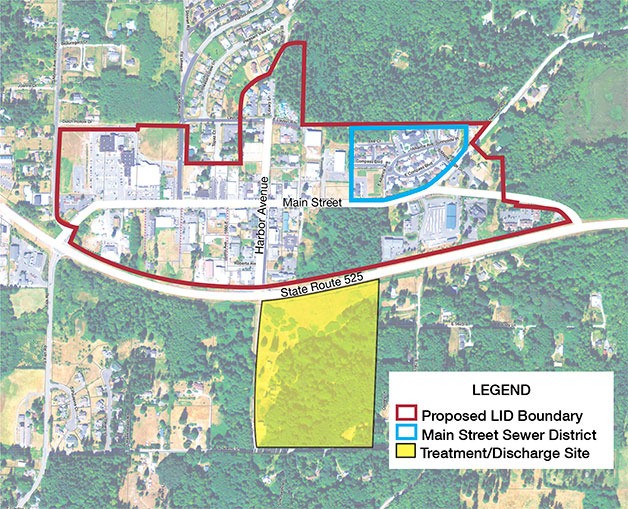

Sewer commissioners have since scaled back the effort into a series of phases, beginning with the commercial core, an area stretching from Chase Bank on Main Street to the intersection at Scott Road and Highway 525. While only a fraction of the larger Freeland NMUGA, it’s the area of the most intense commercial development and expected to see the most benefit.

Cost of phase 1 is projected at $9.9 million. With the state grant money, a funding gap of $6.5 million has been identified, about $1.3 million of which would be picked up by commercial core property owners.

A recent meeting with the Freeland Chamber of Commerce and district officials, however, proved some business leaders remain unconvinced by the plan moving forward. The concept of sewers is largely supported by the commercial district, but details of the plan remain in dispute.

One point of contention is that the coverage area of phase 1 is too small, according to Chet Ross, chamber president.

“It’s about half of the [true] commercial core,” he said.

Ross, who was a leader in the failed 2010 effort, contends that many businesses to the west of the existing plan boundary have expressed a desire to be included but will be left out.

Similarly, Gary Reyes, a chamber board member and owner of storage business, questioned the district’s plan to merge with the Main Street Sewer District. The idea is to decommission the smaller district’s treatment system and mitigate elevated nitrogen levels in drinking water wells. Reyes said it may make more sense to let that district handle its own problems and use resources to cover more of the commercial core.

Also concerned about the project is commercial property owner Al Peyser. At the board’s meeting Monday, he urged the commissioners to lobby the county to improve development regulations in Freeland. Time is of the essence, he said, because unless people know what they can do with their properties, they won’t be inclined to support a sewer project.

The effort to build sewers has gone on long enough, he said, and this effort simply shouldn’t fail.

“We’ve been after sewer systems for 20 years and haven’t been able to make it happen,” Peyser said.

According to Malzone, sewers for a larger commercial area were considered, but cost and growth estimates simply didn’t make it supportable. The outlined area contains 77 acres, and about 30 percent of it is undeveloped.

As for merging with another district and development regulations, he said the nitrate problem in drinking wells is Freeland’s problem while rules about what can be built are the county’s. One problem the district can address, but the other is out of its hands.

Another, more immediate, problem is money. The district has a large funding gap to address. Also, the state grant expires this December, which means commissioners have a narrow window to either spend the money, begin construction or show significant progress before the grant expires.

If the feasibility study shows the site fails to meet criteria such as daily capacity minimums, then the district may need to look elsewhere. Officials are optimistic the site will prove satisfactory, but a significant setback could translate to funding headaches.