Rockie Eggebrecht is a hard-working farmer, but not the kind who wears overalls, labors in the soil and grows broccoli. He wears street clothes, works indoors and plants exclusively in pea gravel.

He grows recreational marijuana, and he loves his job.

Eggebrecht, 50, has been producing and processing pot lawfully since April. His business, north of Oak Harbor, is called Rock Garden, a play on his name and an allusion both to his hydroponic method and to the act of getting stoned.

“I’m damn proud of what I do,” Eggebrecht said during a recent visit to his growing operation. “I won’t put out a product that doesn’t meet my standards.”

“I want to supply gourmet marijuana to the market.”

Initiative 502, voted into law in November 2012, decriminalized recreational marijuana. As of Oct. 23, 14 Island County residents or companies had sought licenses to grow recreational pot, but only four had apparently received them, according to data from the Washington State Liquor and Cannabis Board (see box).

Nine county residents or companies applied to process pot, some of whom also seek to grow it.

Recreational marijuana sales to the public began July 8, 2014, in much of Washington state and, on Oct. 24, 2014, on Whidbey.

Growing pot is a good way to make a living, and maybe even to get wealthy, Eggebrecht said. He hopes to gross $8,000 a month and be earning six figures within two years, though he’s only breaking even right now. Seven figures “is not possible — I’m doing everything I can to keep up,” he said.

“I just want a decent lifestyle. I can do this until I want to retire.”

But it’s not for everyone. A disciplined and hard-working entrepreneur, he works seven days a week.

Rock Garden has 1,200 square feet of growing space under one roof, every inch of it covered by closed-circuit TV cameras as required by law. He could expand up to 2,000 square feet under his license, but works alone, with only the occasional assistance of his wife, so “this is about as much as I can handle.”

Though he hopes his wife will join him someday soon, she is working a full-time job elsewhere for now. And he wouldn’t consider taking on employees, because that could jeopardize quality, he said. It would also cut profits.

Before starting Rock Garden, for 21 years Egge-brecht held various jobs at Dri-Eaz, a Burlington maker of equipment for drying flooded buildings.

For 10 years before, he grew bell peppers, lettuce, jalapenos, strawberries and tomatoes in his indoor facility, all hydroponically — using water and nutrients but no soil. That’s how he honed his method for growing pot.

His “grow” is housed in a building behind his home. Walking from the office/processing room into the growth area, visitors are required to sign in, wear a visitor’s badge and slip booties over their shoes.

The sign-in and badge are state requirements. The booties are his own.

“If you’d come from another grow, I’d make you wear a full-body suit,” he said. “Spider mites can decimate a crop in nothing flat, and I don’t use pesticides.”

His operation is almost antiseptically clean. Fans warm, cool and circulate the air. Dehumidifiers prevent mold.

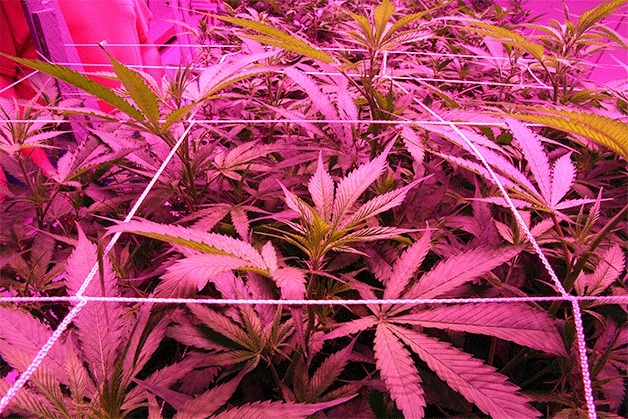

To move into marijuana cultivation, Eggebrecht in-vested about $140,000, a big part of which went to the overhead banks of cool-running, high-intensity Illumetix-brand LED lights, which give off a reddish hue up to 18 hours a day to provide the plants with just the right frequency they need to thrive.

The lights cost about $1,500 every two months to run — half the cost of halide lights.

Walking into the flowering room, one’s nostrils are tickled by the pungent or sweet scents of the growing plants. Eggebrecht grows eight strains, with intriguing names like Black Russian, Blue Dream, THC Bomb, Strawberry Blue and Mastodon Kush.

All are between 20 and 25 percent THC, the active ingredient in pot. They differ in taste, smell, smoothness and the high they produce. Most are hybrids with varying proportions of sativa and indica, the two species of marijuana, each of which has a different effect.

Higher THC content does not necessarily mean a faster or stronger high, he said.

Vintners can spit out samples they’re testing. Pot growers have to inhale.

“You can’t avoid getting high, and I smoke every day, but at least I only smoke one strain at a time,” Eggebrecht said.

That helps him better evaluate samples for quality.

Exclusivity of strains is an important competitive advantage. He reported happily that another Washington grower has 250 strains, only two of them the same as his own.

Legal restrictions make it difficult for other growers to get his strains.

He currently sells his products to four stores, one each in Bellingham, Mount Vernon, Oak Harbor and Stanwood. Demand is matching up well with supply, he said.

Eggebrecht uses nothing more complex than a pair of scissors to harvest his plants, which can number up to 1,000 at a time.

Some growers use machinery for an initial harvest, he said, but that leaves a lot of leaf among the flowers. Trimming takes about 75 percent of his time, he said.

After being harvested, the flowers are hung to dry for five to seven days. Then they have to pass both in-house and out-of-house quality assurance. Those deemed salable are stored at room temperature in airtight containers.

They’re packaged only when ordered.

Ready-to-sell Russian Blue flowers have a delicious, fruity smell. Mastodon Kush smells earthy.

His pure flower wholesales for $4 to $4.50 a gram and retails for roughly $15 a gram, including the 37 percent tax imposed on retailers by the state.

There is no market for any part of the plant except its flower, or bud.

Flowers are consistently coated with trichomes, the crystal-like sticky hairs that produce the active ingredients. Baby-boomers who last smoked pot in the 1970s have probably never seen them.

Leaves and “less beautiful” flowers go toward producing his hash, his only other product. He wholesales it for $10 a gram. He won’t make edible products, such as pot-infused candy, because “I’m into keeping it as pure as the product can be.”

But he may begin producing pre-rolled joints, to satisfy customer demand, he said.

What worries Eggebrecht most about his operation is the vagaries of state law.

“Some rules are clear-cut and some are interpreted. You constantly have to be watching to make sure you’re operating within the law.”

Oak Harbor’s Kaleafa, a retailer, enjoys working with Rock Garden, said co-owner Brent Qualls. “He consistently delivers great service and a great product,” Qualls said of Eggebrecht.

“His customer service is arguably the best of any vendor we work with, and we like to support him because he’s local.”