Everybody knew.

Or at least very few Oak Harbor decision-makers can legitimately claim they had no prior knowledge of a known archaeological site near SE Pioneer Way, according to city documents obtained through a Whidbey News-Times public records request.

If they didn’t work on the project directly, they were provided with documents that revealed both the site’s existence and the warnings of state regulators to take the appropriate steps before construction began. Those who received the information include every single member of the city council.

The records reveal that some city officials, primarily project leaders, have known about the site for years, as far back as 2007, and that they received repeated warnings from the city’s own hired consulting firm to follow the state’s recommendations regarding the handling of Native American remains.

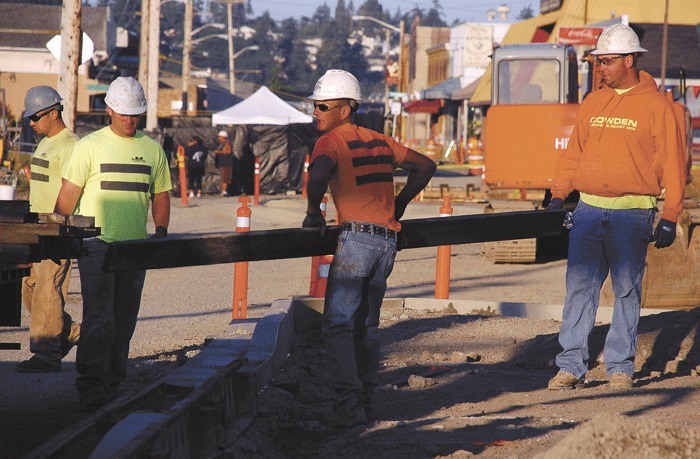

While it’s still unclear why none of the suggestions were followed, the subsequent discovery of Native American remains on SE Pioneer Way this past June has put the city’s $7.75 million downtown road project at least a month behind schedule, racked up more than $200,000 in unexpected bills, and may have left Oak Harbor vulnerable to lawsuits.

Bones not new

The discovery of Native American remains in the downtown area is nothing new. Over the past 50 years, at least two city projects on or very near SE Pioneer Way have resulted in inadvertent findings.

According to a Whidbey News-Times story published in 1962, remains were unearthed while crews were installing a waterline for a bathhouse near City Beach Street. Former city worker Joe Tyhuis was photographed holding a skull.

Twenty years later, in 1983, another Whidbey News-Times story reported a second discovery. But this time bones were found on SE Pioneer Way in nearly the exact same spot as the current dig site in front of the Oak Harbor Tavern and Mike’s Mini Mart.

The location is adjacent to the archaeological site officially cataloged by the state as 45-IS-45. The state Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation documents it as an early “Skwadbsh” settlement, though exactly when it was first recorded is uncertain.

However, it is clear that city planners and engineers have known about the site for years. An archaeological assessment of the area surrounding Flintstone Park was completed in February of 2007 and submitted to the Federal Transit Administration in association with the municipal pier and park improvement project.

Prepared by Matthew Gill of Western Shore Services Inc., the assessment claimed the site was first documented “based on information from long-time residents and that no evidence was apparent over 50 years ago when the site was first recorded.”

Following an investigation, which found no indications of archaeological deposits or significantly historical features, Gill determined that the pier project could move forward without any negative impacts to cultural resources despite the project area falling within the 500-foot buffer surrounding the archaeological site.

Site discussed

While discoveries in the 1960s and 1980s can be lost or forgotten, especially when most if not all those workers have retired, site 45-IS-45 was discussed again by Pioneer Way project leaders beginning in 2009.

The first mention of the site, detailed in the thousands of pages of project documents supplied by the city, comes on March 5 following research conducted at the state Historic Preservation Office.

The research was conducted by officials from Perteet, the Seattle-based consulting firm the city hired to perform early design and permit work for the downtown road project.

On May 22, following the submission of a cultural resources review form, the state Historic Preservation Office sent Russ Pabarcus, an Oak Harbor civil engineer who is no longer employed with the city, a letter stating that no additional archaeological survey work was needed as it wouldn’t “provide useful or reliable information about the presence of archaeological deposits in the project area.”

“Instead, we strongly recommend you retain the services of a professional archaeologist to monitor and report on ground disturbing activities,” transportation archaeologist Lance Wollwage wrote.

He also suggested the city create an Inadvertent Discovery Plan to address anything found and to inform concerned tribes of the project.

In June, Perteet senior project manager Mick Monken emailed Pabarcus saying that the city isn’t required to follow the state’s recommendations because only local funds are being used on the project.

However, Monken suggested they be followed anyway as it would put the city in a better legal position if something were discovered. He identified the cost of archaeological services at about $14,000, but said he would need authorization before moving forward.

On July 12, Perteet acknowledged a city directive to contact the tribes, though city records do not make clear where the direction came from. The Perteet memo indicated that it wasn’t a “critical item” just yet, but that the company would need formal approval before taking any action.

The following month, on July 29, Pabarcus emailed Monken back, questioning the need to do anything more than inform the tribes. He cited Gill’s assessment, saying it satisfied the “Feds” for the pier and park project and questioned why it couldn’t do the same for this project.

The email was also sent to City Engineer Eric Johnston.

Monken sent a reply to Pabarcus and Johnston the same day. He encouraged notification of the tribes and explained again the risk of not following the suggestion if something is found.

“In this event, there are several exposures that could include: the contractor having lost time and the potential associate damage claim, litigation from the tribes for not having an action plan on how to deal with the event, public litigation for not taking recommended actions by the DAHP, and not having the support of DAHP to support the city in a defense,” Monken wrote.

Through the cracks

No additional mention of the issue could be found in the city documents until April 30, 2010, when Perteet Planner Stephanie Hansen emailed Pabarcus and Johnston a draft State Environmental Protection Act checklist.

It contained acknowledgement of site 45-IS-45 as well as the state’s recommendations. Hansen also included the historic preservation office’s letter.

“Be sure to check over this section, as I assume you will be taking these actions,” Hansen wrote.

On Aug. 3, 2010, Oak Harbor Senior Planner Ethan Spoo sent an email to Planning Director Steve Powers, Johnston and Pabarcus, saying he had reviewed the checklist and proposed five conditions. None include the state’s recommendations.

Three days later, on Aug. 6, Powers issued a mitigated determination of nonsignificance based on Spoo’s recommended conditions.

Over the next three months, the checklist, which had been modified to exclude the state’s recommendation to contact the tribes, was included in agenda packets that went before the planning commission on Sept. 28 and the city council on Nov. 16.

The checklist with the recommendations was included as attachments, background information, for approval of a required Shoreline Substantial Development Conditional Use Permit.

Signing off on the council’s agenda item was Mayor Jim Slowik, City Administrator Paul Schmidt, Finance Director Doug Merriman, and City Attorney Margery Hite.

All seven city council members were in attendance at the meeting and approved the permit by unanimous vote.

What happened?

So why weren’t the state’s recommendations followed? It appears that answer will have to wait. While the city documents do show who knew about the archaeological site and the state’s recommendations, along with its progress through the city’s permitting process, they don’t reveal how or who dropped the ball.

City officials are also remaining largely mum on the topic. In June, the state Historic Preservation Office released Wollwage’s 2009 letter with its warnings and recommendations, and a statement from the mayor’s office quickly followed.

It confirmed the state’s suggestions were included in permit documents but that they ultimately weren’t followed. It also reported that Slowik had asked for a review of the city’s process to find out what happened. That was over two months ago.

City Administrator Paul Schmidt, who is conducting the review, said he had hoped it would be complete before the end of the week. However, on Friday he said it was not finished and that he was considering expanding the scope of the review.

He, along with City Engineer Eric Johnston, have declined to comment until the review is complete. Schmidt said he felt it would be inappropriate to report any findings to the press before going first to the city council.

Similarly, Mayor Jim Slowik declined to delve into details of the review. However, he did say he was not relieved by what he’s learned so far. Slowik said Friday morning it has become clear the fault was not with Perteet but with the city.

“I think the review is going to point out that the city made a significant error,” Slowik said.

“I’m not happy about the result; the result is a mistake,” he said.

Along with accepting responsibility for the mistake, Slowik said the review will contain suggested policy changes to ensure such an error is not repeated in the future.