Coupeville’s iconic red wharf has been standing for almost 120 years, representing a source of pride for the local community and an important tourist attraction.

Local officials, however, are uncertain whether it will still be around 120 years from now.

About a month ago, the wharf was granted “endangered” status by the Washington Trust for Historic Preservation. With the dangers posed by sea level rise predictions and the increasing king tides, the wharf risks being flooded by 2050, according to Coupeville’s 2023 Sea Level Rise Vulnerability Assessment.

The solution to these looming threats: raising the wharf by four to five feet, a project that is estimated to cost the Port of Coupeville $5 million, according to Executive Director Chris Michalopoulos.

After the port’s request for state funding to raise the wharf was denied last month, this designation brings some good news.

According to Michalopoulos, this status will help the port — which has owned the wharf since 1969 — secure grant funding in the future. Furthermore, he said, it allows the port to network with other owners of historic properties, sharing experiences and resources.

Without money from the Community Project Funding — for which the wharf competed against 14 projects — Michalopoulos said the port now needs to figure out how to come up with the sum. He believes the issue needs to be addressed within the next five to 10 years, but it’s still unknown when the project will kick off.

“To give you a date is almost impossible,” he said. “You never know, even if you got state funding, when you’re actually able to access those funds and go after those funds to support your project.”

The idea of raising the wharf was first discussed in the winter of 2022. According to the executive director, the technology that would be implemented to raise the wharf exists and has been used in the past.

Michalopoulos said the project will consist of cutting the supporting piles and running steel beams under the structure. A series of hydraulic lifts will use the beams to lift the wharf. Once the wharf is at the desired height, the piles will be spliced and extended with steel piles.

The causeway, which connects the wharf to the shore, might also need to be lifted, though that still needs to be determined.

“When they raise this building, they will do it extremely slowly,” he said.

Though there isn’t an official plan in place yet, Michalopoulos assumes businesses would have to close down while certain parts of the project are underway.

Currently, the wharf is undergoing a series of renovations to address the wharf’s vulnerabilities and damages caused by storms, work that is expected to be completed by the end of 2025. A new roof was installed in 2023, while a complete window and door rehabilitation is scheduled for mid-September, Michalopoulos said.

Replacement of the dock, which is “years past its lifespan,” is expected to start by the end of this year. The wood piles will be replaced with steel piles, removing the creosote wood currently in place.

Recently, the port installed new fuel tanks that are accessible to the public.

While helpful, these improvements don’t protect the wharf from the impact of “masses of water” and logs hitting its structure.

In his seven years serving the Port of Coupeville, Michalopoulos has witnessed natural events that made him feel “concerned about the wharf, its location and Mother Nature,” including a storm that took away 25 to 30% of the roof tiles, and a king tide that caused the dock to sit higher than the deck.

The Coupeville Wharf, he said, is the “last of its kind.”

The wharf was built in 1905, about 55 years after the first Europeans settled on Central Whidbey, and is the town’s only remaining wharf. According to writings by the late historian Roger Sherman, Coupeville has had at least five wharves built at different times, including Robertson’s Wharf, Happy Jack’s Wharf and Pearson Wharf, though it’s unclear if there were more.

The surviving wharf was used for a variety of purposes, including supplying fuel for wood-burning steamboats, exporting and importing goods with the mainland, storing grain and serving “mosquito fleet” passengers as a ferry terminal.

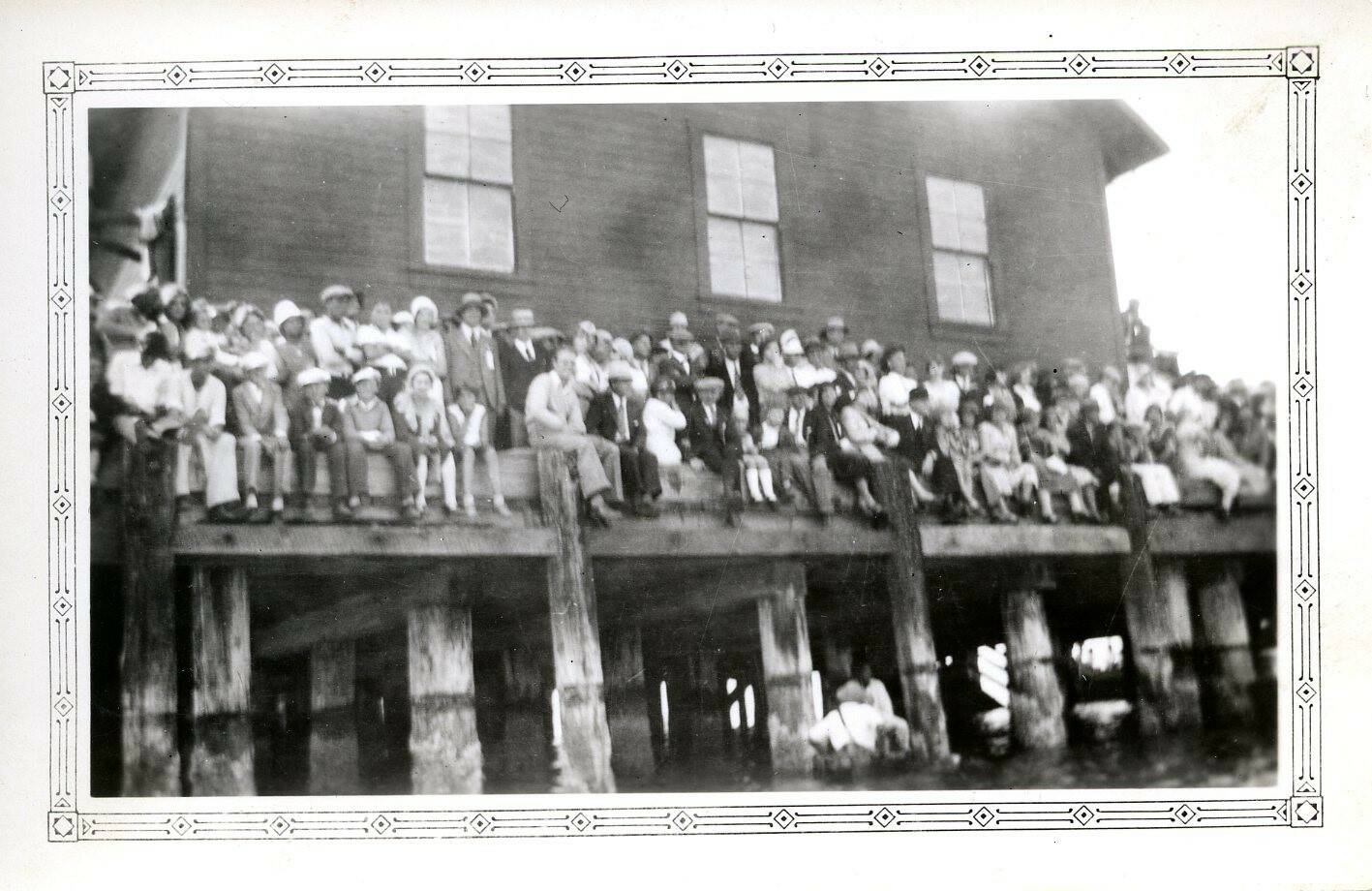

It was a place where community members would gather to socialize, learn the latest news and pick up their mail. Children, Sherman wrote, would beg their parents to take them to the wharf, where former owner Elmer Calhoun would allow them to jump off the roof and railings, plunging into the water. Calhoun, who owned the wharf between the early 1900s and 1949, was among many other things a gold miner, hotel owner and the town’s mayor for 16 years.

Kids also enjoyed fishing at the wharf. Thirteen years after the steamboat service to Whidbey was discontinued, Calhoun sold the wharf to Richard Hansen, who would let children fish through the restroom holes when it was too cold outside.

In the past, the wharf’s “toilets” consisted of holes in the floor, where human waste would be “flushed” by the tides below.

Hansen named the company “Coupeville Wharf and Seed Company,” according to Sherman. Hansen was also a farmer, and his wife Faith Hansen and their seven daughters helped him on the dock and the farm.

In the 1950s, Hansen installed two mills to screen seeds from a grass that was growing more popular on Whidbey, known as Alta Fescue. Hansen would then truck the seed to Seattle.

Sherman recalled when Hansen created a depression in the dock that trucks would back into, so the truck floor would be at the same level of the wharf floor, thus making unloading easier. For drivers, including a teenaged Sherman, it was a scary endeavor as they had to lean over the water to enter and leave the truck cab.

Hansen later removed the ramp, built a lift for small boats and used the warehouse for storage, Sherman wrote.

The Hansens sold the wharf and the tidelands to the Port of Coupeville in 1969.

Over time the wharf has gone through various repairs and has changed its look, adding and removing a tower used to process grain, installing new floats, replacing the holes on the floor with real toilets and making space for retail stores, eateries, a fuel station and a marine mammal exhibition.

Vern Olsen, a volunteer at the Island County Historical Museum in Coupeville, said the wharf is an important piece of Coupeville’s history. Coupeville is one of the state’s oldest towns, and has kept its historic character, giving people an idea of what it used to look like and inspiring a sense of local pride.

“Coupeville is definitely the center for history on Whidbey Island,” he said.

Yet many residents don’t know the town’s history, which is why Olsen believes it’s important to preserve the last wharf in the “City of Sea Captains” or, as Sherman named it, the “City of Wharves.”

“I do not want to ever say its future is uncertain,” Olsen said. “I’m saying, ‘Let’s make it happen.’”

Note: The online version of this story was edited to include Richard Hansen, former owner of the wharf.