Kati Corsaut’s professional resume reads something like the chapter outline of an action-packed thriller.

From escorting reporters through the compound at which Charles Ng and Leonard Lake committed as many as 25 brutal murders to awaiting the announcement of pardon or time of death of an inmate in the execution chamber at San Quentin or speaking from the front lines of the Northridge earthquake, Corsaut was there.

In the art of disseminating information from tragedy, she was an adept professional, renowned in her field.

“I think I felt I had to convey what was occurring,” she said, noting that she remained as objective as possible regardless of the situation.

“I felt very, very fortunate to have had the jobs that I had,” she said. “I was never bored.”

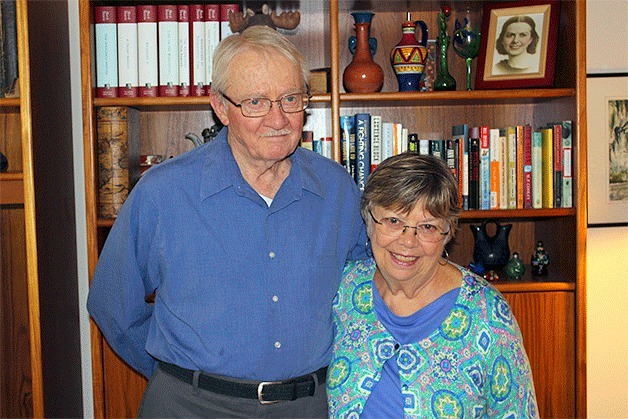

It seems natural, therefore, that post-retirement life for Corsaut and her husband, Alan Jones, should involve being on site for more hurricanes than games of bridge.

Corsaut and Jones began their careers as journalists, eventually transitioning to jobs in communications for government agencies. Jones stayed in that vein of work and worked for the State Department of Water Resources.

Corsaut worked in communications for several government departments, including the State Department of Law Enforcement — Narcotics, the California Attorney General’s Office, the Governor’s Office of Emergency Services and FEMA, as well as the California Department of Corrections.

After retiring from the latter in 1998, Corsaut returned to work as the assistant director of the Communications Office for the California Department of Corrections in 1999, filling in until a permanent replacement could be secured.

Corsaut was ultimately recognized for her hefty list of accomplishments with a lifetime achievement award.

After retirement, both Jones and Corsaut began working as public information officers for FEMA, traveling to disaster locations and providing what information was available to the public, small local newspapers and radio stations.

Jones was the first to join in 1995, when he heard about the reservist program.

“Otherwise I would have just been hanging around the house,” he said.

Corsaut had worked with FEMA when she was a public information officer with the state, on disasters like the Malibu fires, and joined Jones in working directly for the agency in 1998.

Combined, the couple responded to 38 disasters since retirement.

The most difficult aspect of the work, Jones and Corsaut said, was living amongst the ruins of a disaster, witnessing residents’ realization that FEMA is unable to fix it all.

“You wind up in some fairly grim places,” Jones said.

Survivors were often distraught and very emotional upon arriving at the emergency centers, where the couple was often stationed.

Recognizing they were limited in their ability to assist was oftentimes difficult.

“You can’t make them whole,” Corsaut said.

“A lot of people were just at a loss of what to do,” Jones added.

Also in the wake of disaster, however, Jones and Corsaut said they witnessed a great rallying of community.

Many groups, including humanitarian and religious groups, would step in to grant the assistance FEMA was unable to give.

“I think you learn people will rise to the occasion,” Jones said. “There are, of course, those who can’t.”

“You come to appreciate how kind people can be,” Corsaut said.

“You really appreciate what you have,” she added. “You see the misfortune of others and you’re glad to be safe and sound.”

The couple moved to Oak Harbor a little over a year and a half ago from California, and now reside at Regency on Whidbey.