I black out when I drive. While I don’t lose blood supply to the brain, there are certainly gaps in consciousness that I cannot believe I drove through without a ticket.

Driving the same routes at the same times amongst roughly the same people becomes blasé, so our transportation-based boredom shuts down the thinking mind while somehow delivering us to our intended destinations in one piece.

Humans are creatures of habit, ostensibly sacks of bones on cruise control. Winners with Teslas aren’t the only ones who experience autopilot; all you really need is a routine. Once modus operandi is in place, pedals and shifters become extensions of the vehicle’s operator, opening up mental room for other stuff that isn’t the large machinery on wheels of which you are nonchalantly driving.

My perpetual passenger is my partner, Rachel. Whether we’re going to Mount Rainier or Sno-Isle library, I know my daydreaming, glazed-over look wholly terrifies her; though scarier still is me in the passenger seat. When I’m not driving, I’m critiquing as if I wish I were.

Most things are out of our control, but that doesn’t stop me from pretending. Despite having no real influence on the motion of the car as a passenger, I’m constantly checking for speed limits, gas levels, merging semis, turn signals, BPMs of the jam in that guy’s jalopy, engine lights, etc. I’m more aware as a passenger than I am as a driver; less when I need to be, more when I don’t.

Traditionally, passengers have it cushy. We judge a car’s faux pas by who’s in the front seat, not by the person in charge of the snacks, pumping the imaginary brakes. The passenger requirements include sitting down and fastening a seatbelt, and even that second clause is a newer addition to the rules. As long as you’re not outside of the car as it pulls away, you’re probably doing a fine job.

I stare out the windshield as if that hyper-awareness has any bearing on the outcome of the tires: without a steering wheel, I’m an impotent man who’s not allowed to stop watching 3D television. I interminably demonize the driver for wrong turns or a temperature choice I’d never make because it feels like they have something that I don’t: a purpose. But even the passenger seat has its merit.

When Rachel rolls through a stop sign or when she refuses to enter an intersection on a light change, my purpose is jealousy: that I didn’t make those mistakes, that I wasn’t the one being noticed and yelled at. Envy comes easy when your jurisdiction is a glove box.

The traffic lights are always greener when someone else has the right of way. I’m a passenger who wants to be a driver, even though I’m a driver who tunes out the fact that he’s driving and all the beeps that come with it.

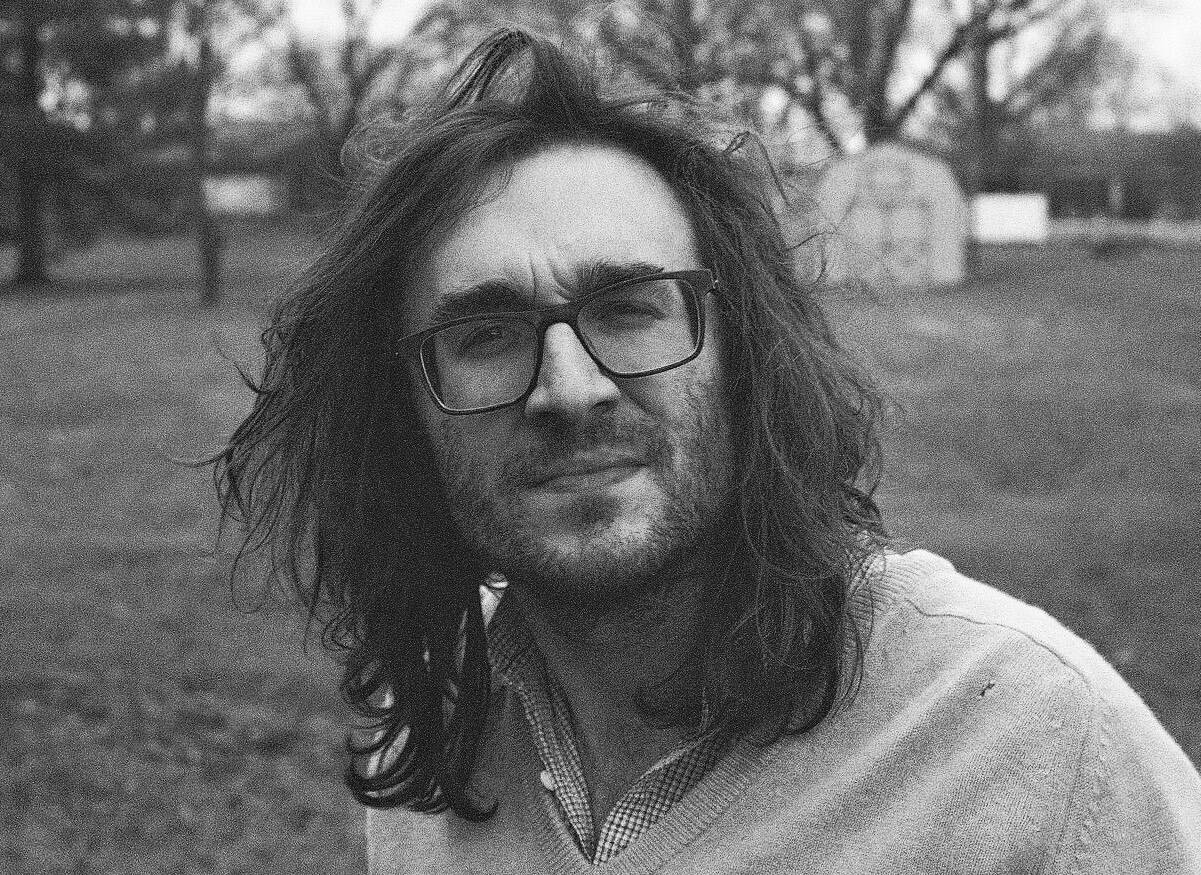

Brandon Berry is a curious newcomer to Whidbey Island who drinks coffee until he’s nauseous. You can reach him at brandonthomasberry@gmail.com.