“Everything was fine. Then one morning the tanks rolled in. Nobody thought it would come to that.”

The 50-something man with perfect English wasn’t describing a third-world coup. His story recalled the moment when he, barely out of his teens, watched a war begin around his Slovenian home in 1991 as Yugoslavia broke apart.

His eyes darkened with sadness and a warning.

“I look across the Atlantic and see the same things building in America.”

My wife and I were on the first day of two-plus weeks in Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Montenegro. That comment shocked us, but we soon lost count of how many times we heard it.

If you’re not worried, you’re not paying attention, they said. All it takes is a spark. Just one spark. Bosnians told of Serb and Croat armies dug in on opposite ridges, shelling the towns in the valleys. We passed a Mostar cemetery packed with gleaming white gravestones dated 1993 through 95. Croatians spoke of ancient Adriatic cities like Dubrovnik, bombed for no reason by Montenegro. We heard, from those who lived through those times, of ethnic cleansing, atrocities, gunpoint evictions, forced marches.

The tale-tellers, almost without exception, worry for America. From halfway around the world they see polarization, extremism, political violence, talk of secession, and public figures who vilify and insult each other. It’s deja vu as they remember the spark that triggered wars that left over 100,000 dead and 4,000,000 displaced.

By the time we headed home I was starting to believe it myself. Could it, will it, happen to our own beloved country?

For answers, and context, I looked to an expert.

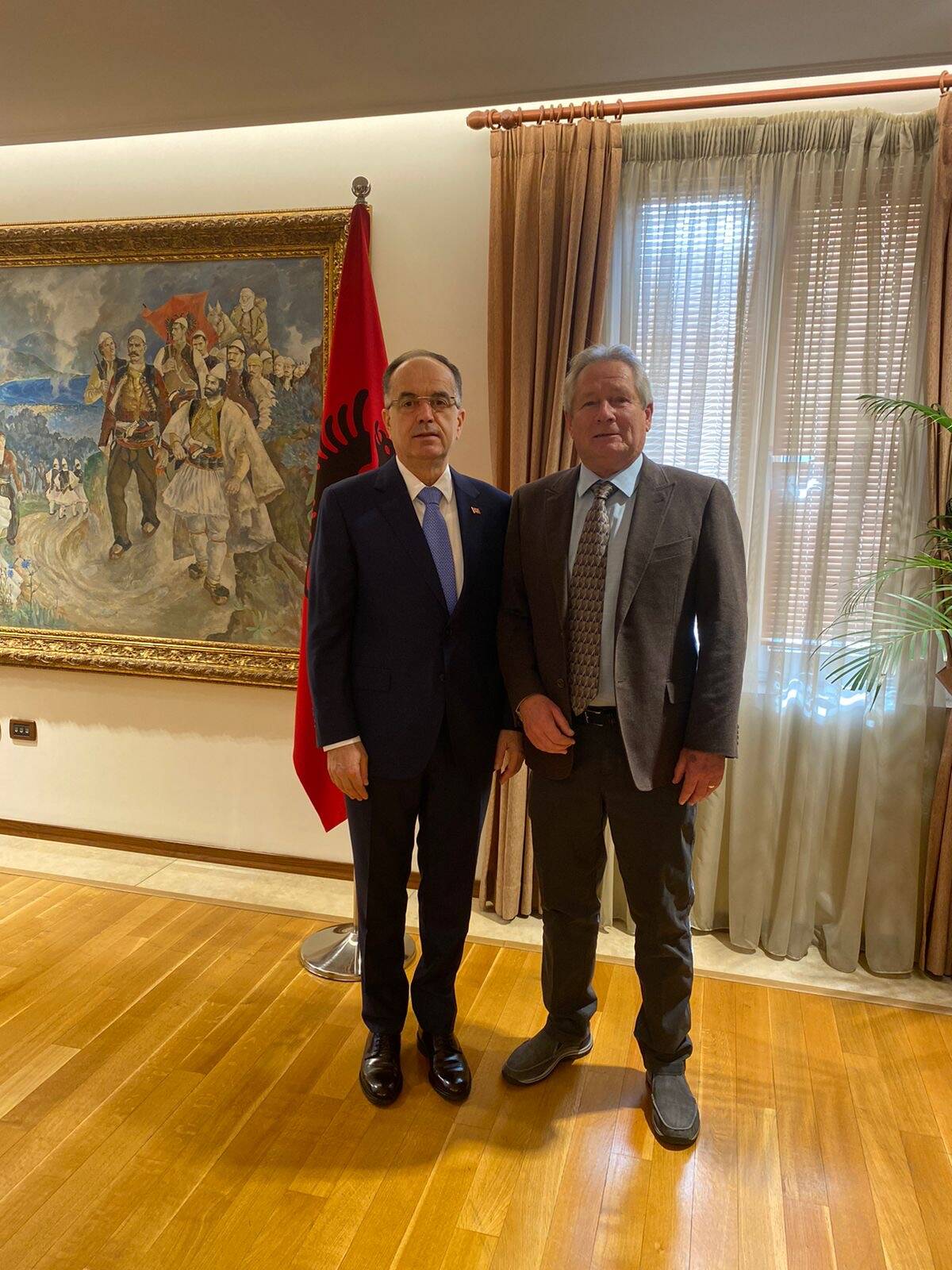

Whidbey resident Bernd Fischer is a retired history professor with a specialty in the Balkan region. He is a member of the Albanian Academy of Science and a special advisor to the Albanian Royal Court. His eight published titles include “A Concise History of Albania and Balkan Strongmen: Dictators and Authoritarian Rulers of Southeast Europe.”

The man knows his stuff, so much so that today, years after retiring, he’s still called on as an advisor and expert witness in Balkan matters. So I asked for reassurance, and I got it.

“The sky isn’t falling,” says Fischer. “The press in that part of the world is notorious for sensationalism.”

More sensationalist than the American press? More than Twitter? You have no idea, Fischer says.

“It’s difficult for people to get clear accurate information. There’s corruption everywhere, and the internet just makes it worse.” So, Fischer says, Balkan people are not only traumatized by their recent memories, they tend to believe their media’s over-the-top narratives about America.

Fischer sees plenty that’s different here compared to the Balkans at their tipping point the late 1980s.

“We’re polarized here, but it’s different,” he says. “Yugoslavia, a relatively young state, faced economic, regional, ethnic, religious and cultural challenges that in the end it simply could not overcome. Our situation is not the same. We will get past this.”

Fischer reminded me that dictator Josip Tito held Yugoslavia together, artificially, for 30 years until his death in 1980. He quashed any hints of separatist movements. When Tito died, the leadership void was filled by people like Serb Slobodan Milosevic. Regional disputes between the six Yugoslav republics finally boiled over after simmering for decades.

“Croats and Serbs were too far apart in background to coexist as countrymen long term,” says Fischer. Croatia tends to be Catholic and identify with the West, while Serbia aligns more with Russia, both culturally and economically.

“Milosevic wanted to annex Serb-majority areas of Bosnia and Croatia, and the Yugoslav army was already filled with Serb officers, soldiers, and equipment,” says Fischer. Serbian aggression led to 10 years of deadly conflicts across the Balkans.

That’s not what’s happening here, and it won’t, Fischer assured me, with a caveat. “Not that we should become complacent; democracy is hard. It requires constant work and participation. But secession movements? Where? How? That’s not realistic. Who? A bunch of guys with ARs? They won’t do well against Black Hawk helicopters.”

Like many Americans, Fischer sees today’s national political discourse lacking competent leadership.

“Going forward, we need people well versed in the political basis of all the branches of government. People who know the system, how it works, and how it’s changed. We can’t recreate the politics of the 60s. It’s a new day.”

Fischer looks to Lyndon Johnson as a leader who maintained strong personal relationships on both sides of the aisle, and brought people together to get things done.

Today, Fischer says, too many politicians move in lockstep with their party and refuse to risk their careers by reaching out to the opposition.

“Conservatives,” he says, “are often more afraid of those on their own right” than they are of liberals. And, he says, gerrymandering by legislators makes polarization worse as districts are drawn to build support for extreme candidates.

All that said about the national stage, Fischer likes what he sees in Whidbey Island politics.

“Elected officials here tend to be pretty moderate. They have to be. If they’re seen as too extreme, they don’t get elected.”

He named a few examples, candidates on left and right, names we’ve seen multiple times on our ballots, who can’t seem to win. In contrast, we discussed a local elected Republican whose recent mailer felt almost liberal on the environment and homelessness. We talked of elected Democrats who are tough on crime, and a conservative official repeatedly pegged as a RINO, who repeatedly wins anyway.

“Whidbey is a unique place politically,” says Fischer, from the Navy base and city environment in the north to the diverse, rural, and left-leaning community to the south. And yet, he says, somehow we find ways to get along. While the rest of America might be far from where we want to be, Bernd Fischer seemed to be saying Whidbey Island is already there. And he ought to know.

After a dark, stormy hour of Balkan worries, the barometer shifted. Fischer’s words of assurance on Whidbey politics brought fresh relief like parting clouds, sunshine, and a salty breeze over Ebey Bluff.

Let’s keep it that way on our island. It’s hard work, but the reward is worth the effort.

William Walker’s monthly “Take a Breath” column seeks paths to unity on Whidbey Island in a time of polarization. Walker lives near Oak Harbor and is an amateur author of four unpublished novels, hundreds of poems and a stage play. He blogs occasionally at playininthedirt.com.